I have become quite interested in analyzing theater, in particular, Broadway and Off-Broadway shows for two reasons:

- I’m struck by the fact that revenue for the show Hamilton is shaping up like a Unicorn tech company

- My son Matthew is producing a show that is now launching at a NYC theater, and as I have been able to closely observe the 10-year process of it getting to New York, I see many attributes that are consistent with a startup in tech.

Incubation

It is fitting that Matthew’s show, Ernest Shackleton Loves Me, was first incubated at Theatreworks, San Francisco, as it is the primary theater of Silicon Valley. Each year the company hosts a “writer’s retreat” to help incubate new shows. Teams go there for a week to work on the shows, all expenses paid. Theatreworks supplies actors, musicians, and support so the creators can see how songs and scenes seem to work (or not) when performed. Show creators exchange ideas much like what happens at a tech incubator. At the culmination of the week, a part of each show is performed before a live audience to get feedback.

Creation of the Beta Version

After attending the writer’s retreat the creators of Shackleton needed to do two things: find a producer (like a VC, a Producer is a backer of the show that recruits others to help finance the project); and add other key players to the team – a book writer, director, actors, etc. Recruiting strong players for each of these positions doesn’t guarantee success but certainly increases the probability. In the case of Shackleton, Matthew came on as lead producer and he and the team did quite well in getting a Tony winning book writer, an Obie winning director and very successful actors on board. Once this team was together an early (beta version) of the show was created and it was performed to an audience of potential investors (the pitch). Early investors in the show are like angel investors as risk is higher at this point.

Beta Testing

The next step was to run a beta test of the product – called the “out of town tryout”. In general, out of town is anyplace other than New York City. It is used to do continuous improvement of the show much like beta testing is used to iterate a technology product based on user feedback. Theater critics also review shows in each city where they are performed. Ernest Shackleton Loves Me (Shackleton) had three runs outside of NYC: Seattle, New Jersey and Boston. During each, the show was improved based on audience and critic reaction. While it received rave reviews in each location, critics and the live audience can be helpful as they usually still can suggest ways that a show can be improved. Responding to that feedback helps prepare a show for a New York run.

Completing the Funding

Like a tech startup, it becomes easier to raise money in theater once the product is complete. In theater, a great deal of funding is required for the steps mentioned above, but it is difficult to obtain the bulk of funding to bring a show to New York for most shows without having actual performances. An average musical that goes to Off-Broadway will require $1.0 – $2.0 million in capitalization. And an average one that goes to Broadway tends to capitalize between $8 – $17 million. Hamilton cost roughly $12.5 million to produce, while Shackleton will capitalize at the lower end of the Off-Broadway range due to having a small cast and relatively efficient management. For many shows the completion of funding goes through the early days of the NYC run. It is not unusual for a show to announce it will open at a certain theater on a certain date and then be unable to raise the incremental money needed to do so. Like a tech startup, some shows, like Shackleton, may run a crowdfunding campaign to help top off its funding.

You can see what a campaign for a theater production looks like by clicking on this link and perhaps support the arts, or by buying tickets on the website (since the producer is my son, I had to include that small ask)!

The Product Launch

Assuming funding is sufficient and a theater has been secured (there currently is a shortage of Broadway theaters), the New York run then begins. This is the true “product launch”. Part of a shows capitalization may be needed to fund a shortfall in revenue versus weekly cost during the first few weeks of the show as reviews plus word of mouth are often needed to help drive revenue above weekly break-even. Part of the reason so many Broadway shows employ famous Hollywood stars or are revivals of shows that had prior success and/or are based on a movie, TV show, or other well-known property is to insure substantial initial audiences. Some examples of this currently on Broadway are Hamilton (bestselling book), Aladdin (movie), Beautiful (Carole King story), Chicago (revival of successful show), Groundhog Day (movie), Hello Dolly (revival plus Bette Midler as star) and Sunset Boulevard (revival plus Glenn Close as star).

Crossing Weekly Break Even

Gross weekly burn for shows have a wide range (just like startups), with Broadway musicals having weekly costs from $500,000 to about $800,000 and Off-Broadway musicals in the $50,000 to $200,000 range. In addition, there are royalties of roughly 10% of revenue that go to a variety of players like the composer, book writer, etc. Hamilton has about $650,000 in weekly cost and roughly a $740,000 breakeven level when royalties are factored in. Shackleton weekly costs are about $53,000, at the low end of the range for an off-Broadway musical, at under 10% of Hamilton’s weekly cost.

Is Hamilton the Facebook of Broadway?

Successful Broadway shows have multiple sources of revenue and can return significant multiples to investors.

Chart 1: A ‘Hits’ Business Example Capital Account

Since Shackleton just had its first performance on April 14, it’s too early to predict what the profit (or loss) picture will be for investors. On the other hand, Hamilton already has a track record that can be analyzed. In its first months on Broadway the show was grossing about $2 million per week which I estimate drove about $ 1 million per week in profits. Financial investors, like preferred shareholders of a startup, are entitled to the equivalent of “liquidation preferences”. This meant that investors recouped their money in a very short period, perhaps as little as 13 weeks. Once they recouped 110%, the producer began splitting profits with financial investors. This reduced the financial investors to roughly 42% of profits. In the early days of the Hamilton run, scalpers were reselling tickets at enormous profits. When my wife and I went to see the show in New York (March 2016) we paid $165 per ticket for great orchestra seats which we could have resold for $2500 per seat! Instead, we went and enjoyed the show. But if a scalper owned those tickets they could have made 15 times their money. Subsequently, the company decided to capture a portion of this revenue by adjusting seat prices for the better seats and as a result the show now grosses nearly $3 million per week. Since fixed weekly costs probably did not change, I estimate weekly profits are now about $1.8 million. At 42% of this, investors would be accruing roughly $750,000 per week. At this run rate, investors would receive over 3X their investment dollars annually from this revenue source alone if prices held up.

Multiple Companies Amplify Revenue and Profits

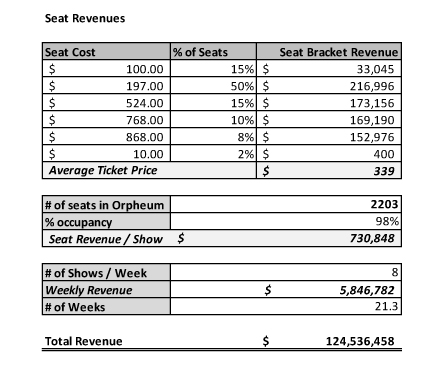

Currently Hamilton has a second permanent show in Chicago, a national touring company in San Francisco (until August when it’s supposed to move to LA) and has announced a second touring company that will begin the tour in Seattle in early 2018 before moving to Las Vegas and Cleveland and other stops. I believe it will also have a fifth company in London and a sixth in Asia by late 2018 or early 2019. Surprisingly, the touring companies can, in some cities, generate more weekly revenue than the Broadway company due to larger venues. Table 1 shows an estimate of the revenue per performance in the sold out San Francisco venue, the Orpheum Theater which has a capacity 2203 versus the Broadway capacity (Richard Rogers Theater) of 1319.

Table 1: Hamilton San Francisco Revenue Estimates

While one would expect Broadway prices to be higher, this has not been the case. I estimate the average ticket price in San Francisco to be $339 whereas the average on Broadway is now $282. The combination of 67% higher seating capacity and 20% higher average ticket prices means the revenue per week in San Francisco is now close to $6 million. Since it was lower in the first 4 weeks of the 21 plus week run, I estimate the total revenue for the run to be about $120 million. Given the explosive revenue, I wouldn’t be surprised if the run in San Francisco was extended again. While it has not been disclosed what share of this revenue goes to the production company, normally the production company is compensated as a base guarantee level plus a share of the profits (overage) after the venue covers its labor and marketing costs. Given these high weekly grosses, I assume the production company’s share is close to 50% of the grosses given the enormous profits versus an average show at the San Francisco venue (this would include both guarantee and overage). At 50% of revenue, there would still be almost $3 million per week to go towards paying the production company expenses (guarantee) and the local theater’s labor and marketing costs. If I use a lower $2 million of company share per week as profits to the production company that annualizes at over $100 million in additional profits or $42 million more per year for financial investors. The Chicago company is generating lower revenue than in San Francisco as the theater is smaller (1800 seats) and average ticket prices appear to be closer to $200. This would make revenue roughly $2.8 million per week. When the show ramps to 6 companies (I think by early 2019) the show could be generating aggregate revenue of $18-20 million per week or more should demand hold up. So, it would not be surprising if annual ticket revenue exceeded $1 billion per year at that time.

Merchandise adds to the mix

I’m not sure what amount of income each item of merchandise generates to the production company. Items like the cast album and music downloads could generate over $25 million in revenue, but in general only 40% of the net income from this comes to the company. On the other hand, T-shirts ($50 each) and the high-end program ($20 each) have extremely large margin which I think would accrue to the production company. If an average attendee of the show across the 6 (future) or more production companies spent $15 this could mean $1.2 million in merchandise sales per week across the 6 companies or another $60 million per year in revenue. At 60% gross margin this would add another $36 million in profits.

I expect Total Revenue for Hamilton to exceed $10 billion

In addition to the sources of revenue outlined above Hamilton will also have the opportunity for licensing to schools and others to perform the show, a movie, additional touring companies and more. It seems likely to easily surpass the $6 billion that Lion King and Phantom are reported to have grossed to date, or the $4 billion so far for Wicked. In fact, I believe it eventually will gross over a $10 billion total. How this gets divided between the various players is more difficult to fully access but investors appear likely to receive over 100x their investment, Lin-Manuel Miranda could net as much as $ 1 billion (before taxes) and many other participants should become millionaires.

Surprisingly Hamilton may not generate the Highest Multiple for Theater Investors!

Believe it or not, a very modest musical with 2 actors appears to be the winner as far as return on investment. It is The Fantasticks which because of its low budget and excellent financial performance sustained over decades is now over a 250X return on invested capital. Obviously, my son, an optimistic entrepreneur, hopes his 2 actor musical, Ernest Shackleton Loves Me, will match this record.