Azure Marketing Day

Each year, Azure hosts a marketing day for CMOs and CEOs of its consumer-facing portfolio companies. This year, on February 27th, we had sessions on the following topics:

- Refreshing Your Brand as the Business Grows

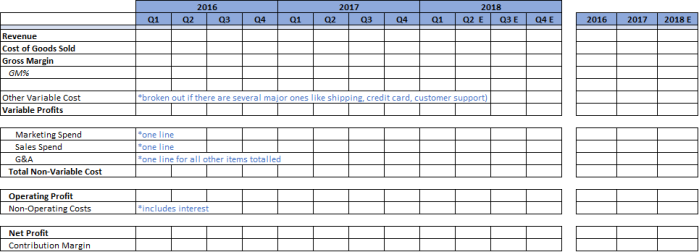

- Metrics for Evaluating Successful Marketing

- Leveraging Comedy to Lower Customer Acquisition Cost

- Know the Next Generation: An introduction to Gen Z

- The Benefits and Drawbacks of a Multi-Channel Strategy

- Influencer Strategies

- Optimizing Pinterest

I presented the one on Metrics, but the other sessions are conducted by a combination of portfolio executives and outside speakers, each a leading thinker on the topic. Since I invariably learn quite a lot from other speakers, it seems only fair to borrow from their talks for a few blog posts so that I can share these benefits.

Much of this post will be based on concepts that I found especially enlightening from the session by Chris Bruzzo, the current CMO of Electronic Arts, on knowing Generation Z. I won’t cite each place I am using something from Chris versus my own thoughts; but you can assume much of the content emanates from Chris. Since Chris is one of the most creative thinkers in marketing, I’m hoping this will make me look good!

Marketers have Defined Generational Characteristics

Marketers often use personas to help understand what they need to do to address different types of customers. A persona may be:

- A married woman 35 years old with a job and 2 children aged 6 and 9;

- A 16-year-old male who is a sophomore in high school;

- A non-working woman aged 50

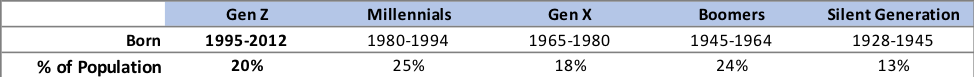

A great deal of research has been done on the characteristics of particular “personas” to better enable a company to create and market products that meet their needs. One categorization of people is by age, with 5 different generations being profiled. The youngest group to emerge as important is Gen Z, roughly defined as those born between 1995 and 2012. Currently the U.S. population over 12 years old is distributed as follows:

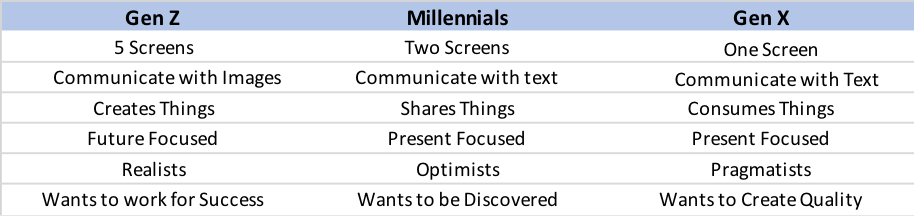

What this means is that Gen Z has become a significant portion of the population to consider when creating and marketing products. With that in mind, let’s compare several characteristics of the youngest three of these groups.

Gen Z is the first generation that are digital natives. They are profiled as having cautious optimism, wanting to be connected, seeking community and wanting to create and control things. Earlier generations, including Millennials, watched TV an increasing number of hours, often multi-tasking while they did. Gen Z has replaced much of TV watching with device “screen time”, including visiting YouTube (72% of Gen Z visit it daily). When asked “What device would you pick if you could have only one?”, GenZers chose the TV less than 5% of the time. Prior generations respond well to email marketing while Gen Z needs to be reached through social media. Gen Z has little tolerance for barriers of entry for reaching a site and will just move on (I feel the same way and think many members of other generations do as well). So, when targeting new customers (especially Gen Z) remove barriers to entry like requiring registration before a user becomes a customer. It is important to demonstrate value to them first.

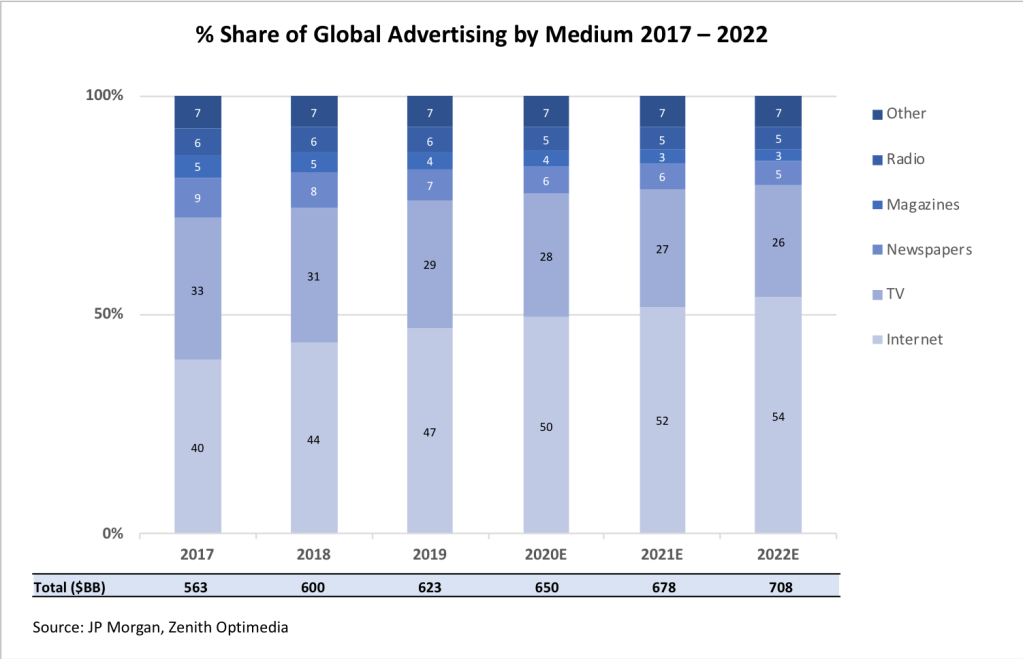

Gen Z grew up in an era where the Internet was part of life and smart phones were viewed as essential… rather than a luxury. On average they spend 40% of their free time on screens. What is even more eye opening is that 91% go to bed with their devices. Advertisers have responded to these trends by gradually shifting more of their spend online. This has been difficult for newspapers and magazines for quite a while, but now it is also having a major impact on flattening out the use of TV as an advertising medium.

There are several implications from the numbers shown in the above chart. First, it is very clear to see that newspapers and magazines as we know them are not viable. This has led to iconic players like the New York Times and Fortune monetizing their brands through conferences, trips, wine clubs, and more. Lesser known brands have simply disappeared. In 2018, TV revenue continued to grow slightly despite losing share as the smaller share was of a larger pie. But in 2019, TV advertising dollars declined, and the decline is forecast to continue going forward. Several factors can be attributed to this but certainly one is that brands targeting Gen Z are aware that TV is not their medium of choice. One unintended consequence of major brands shifting spend to the Internet is that because they are less price sensitive to cost than eCommerce companies, this has led to higher pricing by Facebook and Google.

Personalization is Becoming “Table Stakes” and Offering Co-Creation is a Major Plus

Consumers, in general, and especially Gen Z, are demanding that brands do more to personalize products to their needs and interests. In fact, Gen Z even wants to participate in product creation. One example involves Azure portfolio company Le Tote. The company, much like Stitch Fix, uses algorithms to personalize the clothing it sends based on specifics about each customer. When the company added the ability for consumers to personalize their box (from the already personalized box suggested by the algorithm) there was a sizeable spike in satisfaction…despite the fact that the items the consumer substituted led to a decline in how well the clothes fit! This example shows that using customer data to select new items is only a first step in personalization. Letting the customer have more of a say (be a co-creator) is even more important.

Conclusions

- Startups need to diversify their marketing spend away from Facebook and Google as the ROI on these channels has contracted. At the Azure marketing day, we highlighted testing whether Pinterest, influencers, brick and mortar distribution and/or comedy might be sources that drive a higher ROI.

- If Gen Zers are being targeted, YouTube, Snap, Instagram, and Twitch are likely better places to market

- When targeting new customers (especially Gen Z) remove barriers to entry like requiring registration before a user becomes a customer. It is important to demonstrate value to them first.

- Build great apps for iPhones and Android phones but what is becoming most important is making sure that smart phones work well on your site without requiring an app, as most Gen Zers will use their phones for access. When they do, the mobile web version needs to be strong so that they don’t need to download your app before discovering the value you offer.

- Involve customers as much as possible in the design/selection/creation of your products as this extends personalization to “co-creation” and will increase satisfaction.

Soundbytes

- Readers are aware that I invest in growth stocks (some of which I suggest to you) to achieve superior performance. What you may not be aware of is that over the past 25 years my strategy for investing has been to put the majority of capital in A or better rated municipal bonds (Munis) to generate income in a relatively safe way (and I believe everyone should diversify how they apportion capital). I use a complex strategy to generate superior returns and in the past 25 years I have earned, on average, between 4% and 5% tax free annually. But in the current environment new investments in Munis will have much lower yields so I have started to look at “safe” alternatives to generate income. This type of investment is for income generation and involves a different category of stocks than the growth stocks I target for high returns through stock appreciation.

- Given the recent downturn in the stock market I did my first “bond alternative” investment earlier this week. My goal is to generate income of over 5% on an after-tax basis in stocks that are “safe” investments from the point of view of continuing to deliver dividends at or above current levels.

- My first set of transactions was in Bristol Myers Squibb:

- I bought the stock at $56.48 where the dividend is 3.2% per year

- I sold Jan 21 calls at a strike price of 60 and received $4.95

- If the stock is not called my cash yield, including $1.80 in dividends, would be $6.75 over less than one year which would equal 12% before taxes

- I also sold Jan 21 puts at a strike price of $55 and received $6.46. If the stock is not put to me and is not called that would increase my one-year yield to over 23% of the $56.48 stock price and I would repeat the sale of calls and puts next year. Since my net cost was $43.27 the percentage yield would be over 30% of my cash outlay.

- If the stock was called my net gain would equal the profit on the stock, the dividends for one year plus the premiums on the options and would exceed 30%

- If the stock went below $55 and was put to me at that price I would be ok with that as the new shares would have a net cost of just over $49 with a dividend yield of close to 4.0% (assuming the company follows past practice of raising dividends each year) and I could sell new puts at a lower strike price.

- The second stock I invested in for income is AT&T.

- I bought the stock at $34.60 where the dividend is 6.0% per year

- I sold Jan 21 calls at a strike price of $37 and received $2.05 per share

- If the stock is not called my year 1 cash yield would be $4.13 per share over less than a year or about 12% before taxes

- I also sold Jan 21 puts with a strike of $32 and received $3.30 per share. If the stock is not put to me and is not called, that would increase my one-year yield to over 20% of the stock price and over 25% of the net cash outlay

- If the stock was called, I would only have 3 quarters of dividends, but the gain would be over 30% of my net original cash outlay

- If the stock was put to me my cost of the new shares, after subtracting the put premium would be $28.70 and the dividend alone would provide a 7.2% pre-tax yield and I could sell new puts at a lower price.

- We shall see how this works out but unless they cut the dividends, I won’t worry if the stock is lower a year from now as that would only increase my yield on new stock purchased due to the puts. The chance of either company cutting dividends seems quite low which is why I view this as a “safe” alternative to generate income as I won’t sell either stock unless they are called at the higher strike price.

- I also began reserving capital starting about a month ago as I expected the virus to impact the market. These purchases used about 10% of what I had put aside. I put another 15% to work on Friday, March 13 as the market had fallen further and valuations have become quite attractive – remember the secret is to “buy low, sell high”. When the market is low its always scary or it wouldn’t be low! I do confess that I didn’t sell much when it was high as I tend to be a long-term holder of stocks I view as game changers…so I missed the opportunity to sell high and then repurchase low.