Advanced metrics for Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) and Lifetime Value (LTV)

What is the purpose of CAC, LTV and Payback Period?

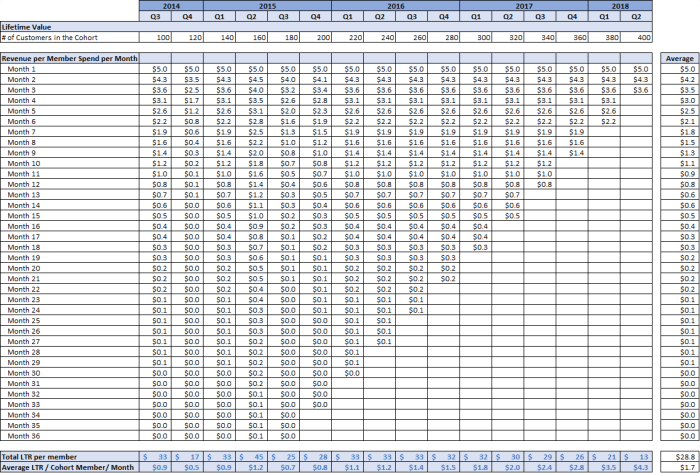

Often entrepreneurs we meet have a list of their KPI’s, but as we dig deeper, it becomes clear that they don’t fully comprehend the purpose of the KPI or why we think that they are so critical in helping us understand the health of a business. I’m a believer in thoroughly understanding the economics of your business, and the metrics around Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC), Customer Lifetime Revenue (LTR), Customer Lifetime Value (LTV) and Payback Period are important metrics to work on improving. In this post we use the word customer to mean a ‘buyer’, someone who actually orders product and will use customer and buyer interchangeably.

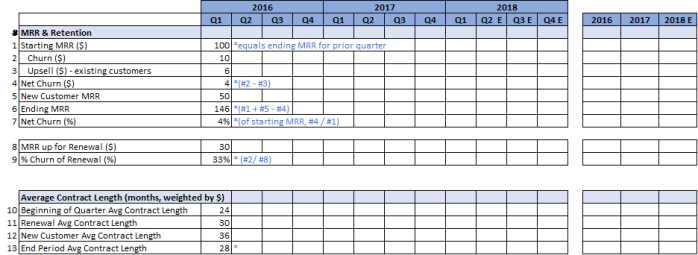

- LTR (Customer Lifetime Revenue) is the total revenue from a customer over their estimated lifetime (we prefer using 5 years as representing lifetime)

- MCA (Marketing Spend for Customer Acquisition) is the marketing cost directed towards new customer acquisition

- CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) captures the cost of acquiring a new buyer

- LTV (Customer Lifetime Value) is the estimated lifetime profits on new customers once they have been acquired

- Net LTV is the estimated lifetime profits on a new customer taking acquisition cost into account or: LTV – CAC

- Payback Period is the time for a new customer to generate profits that equals his or her CAC

When LTV is compared to CAC a measure of the future health of the business can be seen. Most VCs will be loath to invest in any company where the ratio of LTV/CAC is less than 3X and enthusiastic when it exceeds 5X. I also favor companies with a short payback period especially if the recovery is from the first transaction as this means almost no cash is consumed when acquiring a customer.

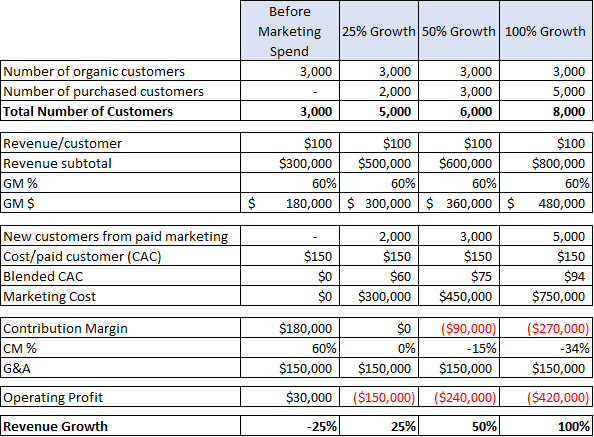

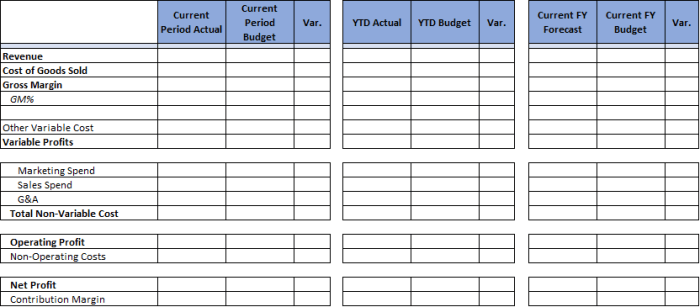

I have previously written about Contribution Margin (gross margin less marketing and sales spend) being one of the most important metrics for companies as it tells me how scaling revenue will help cover G&A and R&D costs. Once Contribution Margin exceeds these costs there is operating profit. A company with low Contribution Margin needs much greater scale to be able to reach profitability than one with high Contribution Margin. Both the LTV/CAC ratio and Payback Period are important predictors of future Contribution Margin levels. Table 1 shows two companies with the same revenue, R&D and G&A cost. Assuming R&D and G&A are fixed for both, at 5% Contribution Margin Company A would need to reach $50 million in revenue to break-even while Company B would be at break-even at under $4 million in revenue given its 65% Contribution Margin.

Break Even Revenue = (R&D + G&A)/ (Contribution Margin %)

For Company A = $2,500,000/ (5%) = $50,000,000

For Company B = $2,500,000/ (65%) = $3,846,154

The problem for Company A stems from the fact that for every $40 spent in acquiring a customer the total LTV (or subsequent profits on the customer) is only $76 making Net LTV $36. With such a low ratio of LTV/CAC, Contribution Margin is also quite low. I’ve chosen two extremes in gross margin to better illustrate the impact of gross margin on Contribution Margin.

Table 1: Illustrative Example on the Importance of Contribution Margin

In a second example, Table 2, we show the impact of much more efficient marketing and remarketing on a company’s results. We assume gross margin, R&D and G&A are the same for Company C and Company D, but that Company D is much more efficient at acquiring and retaining customers, resulting in a lower CAC and a higher LTR and LTV for Company D. This could be due to higher spending on branding and remarketing, but also because they are very focused on the metrics that help them optimize acquisition and LTR. The result is considerably higher LTV/CAC and significantly higher Contribution Margin.

Table 2: Impact of Efficient Marketing & Remarketing on a Company’s Results

A few rules regarding Contribution Margin

- Higher Gross Margin means greater opportunity for high Contribution Margin – for example, Company A at 20% Gross Margin is severely limited in reaching a reasonable Contribution Margin while Company B at 80% Gross Margin has an opportunity for high Contribution Margin and can reach profitability at lower revenue levels

- Companies with many new customers acquired through “free” methods like SEO, viral marketing, etc. have higher Contribution Margins than similar companies with a low proportion of free acquisitions. Notice Company D can spend less on marketing than Company C because it acquires half of its customers from free sources whereas Company C has none from free sources.

- Returning buyers contribute heavily to Contribution Margin since they require little if any marketing cost. A high LTV/CAC ratio usually means customers return more often, which in turn should increase future Contribution Margin. Company D with its very high LTV/CAC likely has much lower churn than Company C and therefore most of its marketing spend is for adding incremental customers rather than just replacing those that churn. If a company simply stopped spending on marketing, its revenue would be from existing customers and new customers acquired from free methods making Contribution Margin roughly equal to Gross Margin. Of course, lack of marketing could have a major impact on future growth

- All other things being equal, companies with short Payback Periods tend to have higher Contribution Margin than those with longer Payback Periods

Marketing Spend on Branding versus Customer Acquisition

Branding is the communication of characteristics, values and attributes of an organization and its products. What is the purpose of spending on branding? To create a strong image of the company and its products so that existing customers want to stay and spending on customer acquisition will be more efficient. Great brands should have a lower CAC and higher LTV than weak brands.

Nike’s “Just Do It” campaign worked well in establishing a brand message that resonated. Their more recent campaign centered around Colin Kaepernick was riskier as it had pictures of the quarterback and the slogan: “Believe in something even if it means sacrificing everything”. While Kaepernick is controversial, he appeals to a large part of the Nike existing and potential buying audience. The campaign helped lift sales by 27% in the first 4 days following the ad launch. Karen McFarlane, founder Kaye Media Partners summed up Nike’s strategy: “Nike’s mission is to bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world. Colin Kaepernick, through his advocacy, conviction, and talent on and off the field, exemplifies those values in the strongest of terms. Couple that with Nike’s commitment to diversity and community, particularly against the backdrop of today’s America where politics have amplified cultural divisions, Nike took the opportunity to lean into their mission and values.”

Marketing campaigns that are for direct customer acquisition differ from branding campaigns as their goal is to directly acquire customers. It is not always clear whether marketing dollars should be classified as acquisition or branding. The key point is that branding is building for the future, whereas acquisition campaigns are measured by how efficiently they deliver current customers. This brings us back to measuring CAC, as the question becomes whether branding campaigns are part of the calculation of CAC. I believe they are not, as CAC should represent the direct cost of acquiring a customer so that increasing that spend will allow us to estimate how many more customers will result. So, I conclude that marketing for branding should be excluded from the calculation of CAC but can be an important strategy to improve efficiency in acquiring customers and maximizing their value. It should be part of the Contribution Margin calculation.

Paid CAC vs Blended CAC

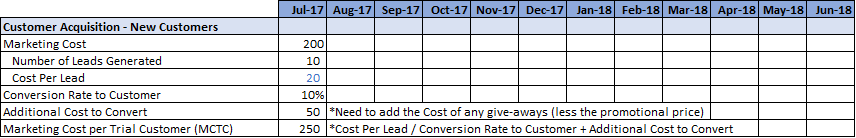

If CAC represents what it costs to acquire a customer, what about those customers that are acquired through SEO, viral marketing, or some other free method? If one simply divides the spend on Marketing for Customer Acquisition (or MCA) by the total number of new customers, the result will be deceptive if it is used to estimate how many more customers will be acquired if MCA spend is increased. Instead companies should calculate CAC in two ways:

Blended CAC = MCA/ (total number of new customers)

Acquisition CAC = MCA/ (number of new customers generated from acquisition marketing only)

Attribution Models and how they help understand CAC by Channel

CAC helps predict the impact of different levels of spending on marketing. Companies also need to know where spending has the best impact, and therefore need to calculate a CAC (and LTV) for each channel of marketing. If a company uses multiple channels like Facebook, Google, and Snap they need to assign credit to each channel for the customers generated from that channel as compared to the spend for that channel to determine the channel CAC. The most simplistic way of doing this is to say, for example, that Google advertising gets credit for the customer if the purchase by the customer occurs after clicking to the site from Google. But what if a consumer sees a Facebook ad, goes to the site to look at products, then a week later comes back to the site from a Snap ad, and then visits the site again because the company sent them an email that they click on, and finally buys something after clicking on a Google ad? Should Google get the entire credit for the customer?

Attribution models from companies like Amplitude and Hive attempt to appropriately credit each channel touchpoint for the role it played in acquiring a customer. For example, a company might assign 50% of the credit to the last touchpoint and divide the other 50% equally among prior touchpoints or use some other formula that is believed to capture how each channel participated in driving that consumer towards a purchase. Attribution models attempt to help companies understand how scaling spend in each channel will impact customer acquisition. For example:

Google CAC = (Google marketing spend)/ (number of customers attributed to Google ads)

One question that arises when using attribution models to credit each channel is whether “free” areas should share the credit when both paid and free touchpoints occur before converting a consumer into a buyer. The issue is whether the free touchpoints would have occurred had the company not spent on paid marketing. In my prior example the customer would never have received an email from the company had they not first seen the Facebook and Snap ads so eliminating these ads would also eliminate the email which in turn probably means they never would have become a customer. In a similar way, someone who clicked on a Google ad but did not buy, might later do a search for the product, and go to the site from SEO and then buy. So, one method of assigning attribution would be to divide the entire attribution among paid channels if a consumer touched both paid and free ones before becoming a customer. If the consumer only went to free channels, then they would count in blended CAC but not as a customer in calculating paid CAC or CAC by paid channel.

Where does Marketing to an existing customer fit in?

CAC is meant to measure new customer acquisition. So, marketing to an existing customer to get them to buy more should not be part of CAC but rather should be subtracted from MCA. I view it as a cost that reduces Lifetime Value (LTV). Many startups ignore the possibility of “reactivating” churned customers through marketing spend. Several Azure portfolio companies have seen success in deploying a reactivation strategy. I consider this spend as marketing to an existing customer and resulting profits an increase in LTV. Revising the definition of LTV (see Table 1):

LTV = LTR – COGS – Marketing Costs to existing customers

MCA (Marketing Cost for Customer Acquisition) = Marketing Costs – branding costs – marketing to existing customers

In Table 1, remarketing expense is 1% of Lifetime revenue for both Company A and Company B or:

Company A LTV = (GM% – remarketing%) X LTR = (20% – 1%) X $400 = $76

Company B LTV = (80%– 1%) X $400 = $316

What about new customers that return the product?

This is a thorny issue. If a consumer buys their first product from a company and then returns it, is she a customer? I think it would not be wrong with interpreting this either way. But I prefer considering her a customer as she was a buyer, and while the return zeros out the revenue from that purchase, she did become a customer. There is ample opportunity for marketing to her again. Considering her a customer lowers CAC as there are more customers for the spend, but it also lowers LTV for the same reason. So, if the interpretation is applied consistently over both CAC and LTV, I believe it would be correct.

More mature companies should apply the methods shown here to better understand their business

By better understanding acquisition CAC and LTV of each channel of customer acquisition a company can direct more spending to the most efficient ones (those with the highest LTV/CAC). By experimenting with “reactivation” spending a company can determine if this improves LTV/CAC. Companies that improve LTV/CAC will likely generate higher Contribution Margin. Those that increase the proportion of customers acquired for “free” can also improve Contribution Margin. Improving CAC and LTV can be accomplished in several ways as described in prior posts:

Optimizing the cost of customer acquisition modeling metrics to drive startup success (March 2014)

How to improve Contribution Margin (Nov 2018)

Without proper metrics a company is essentially flying blind and will be far less likely to succeed. This post provides a blueprint towards a more sophisticated approach to understanding any business.