I have always taken a research driven, multi-pronged approach to identifying attractive publicly traded equity investments, and after reflecting on this approach with a new fund that I am starting, I figured that it would make for an interesting blog post to share this with a broader audience. The companies that I have covered through previous blog posts have been identified through this process. As you likely know if you made some investments based off of my suggestions in the past, they have performed very well!

My Screening Process

I begin with a screening process as follows:

- Discover trends that are disruptive to entrenched market participants, expected to continue for over five years, and relate to very large markets

- Identify companies that are strong beneficiaries of these trends; and

- Evaluate these companies’ competitive advantages that stem from one or more of:

- superior technology often protected by patents,

- strong emerging brand,

- network effect of having built a massive connected audience,

- high quality leadership,

- products that are very difficult to replicate, and/or

- advantageous business model

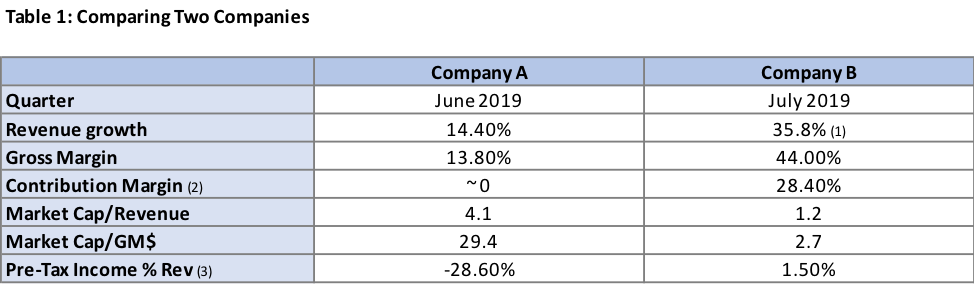

Companies are identified that pass the above screening. Then I apply a filter to reduce these matches to ones that also are already generating or have an ability to generate strong profits. I believe that the most important metric to evaluate companies that have yet to develop mature business models is contribution margin, i.e.: gross margin minus customer acquisition cost. We have covered contribution margin in past blog posts. Check our post in January 2020 which contains our discussion of sophisticated valuation methodology for more background on how I see this as a key metric for evaluating business models.

Companies passing the above screen are rare and, thus, are both difficult and time-consuming to identify. Each company selected from those that passed the screening will also need to have well above average revenue growth for their respective stages.

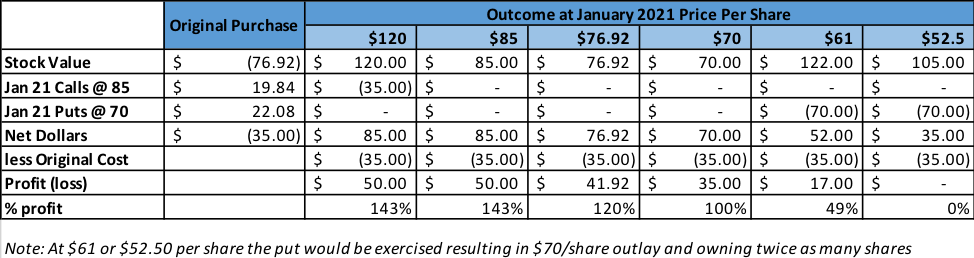

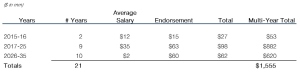

My experience indicates that great returns will be realized over a long period of time from companies that have the key attributes described above and, therefore, I expect, generally, to hold the core of each of my positions for an average period of five years or more. This doesn’t mean never selling any shares, but rather holding the majority of shares for that period. I augment my equity investments in portfolio companies by writing both call and put options or other derivatives (we covered an example of this recently with Zoom in my 2020 predictions). Doing this hedges risk of short-term market fluctuation and generates income from option premiums going to zero over the life of the option. Given my concentration on relatively few securities of high growth companies, it is expected that volatility in my portfolio could often exceed that of the overall market. Therefore, I believe it’s important to avoid margin borrowing as this would increase risk and volatility beyond what I think is an acceptable level.

Applying the Strategy to Investing

The first step in my strategy is to identify longer term trends that are disruptive to entrenched leaders of large markets. I believe the following qualify:

- Growth of eCommerce: Online purchasing will gain share for another 10 years or more

- Shift of services from physical, in-person to virtual: This reduces cost and adds convenience and should persist for many years

- Use of video conferencing in place of older audio conferencing: Will continue to further penetrate businesses and also emerge as a “must have” for individual households

- Online advertising: It will continue to gain share from other forms as it allows for more precise measurement of effectiveness and promotes immediate ability to purchase

- Shift from old generation autos to eco-friendlier (i.e. electric) with software capabilities tightly integrated: It is in its early stages and will gain increasing traction for several decades to come

- The entire online security industry will not only grow at an accelerated pace but also face an upheaval as more modern technology will be used to detect increased attacks from those deploying viruses, spam, intrusions and identity theft

- Web Services will continue to experience double digit growth: Since its directly tied to Internet traffic driven by increased eCommerce, escalation of video, social and virtual services

Several companies that I have selected (and outlined in the past) benefit from more than one of the 7 identified trends and all are one of the dominant players in their particular arena. It should be noted that the arena may be more specific than the trend.

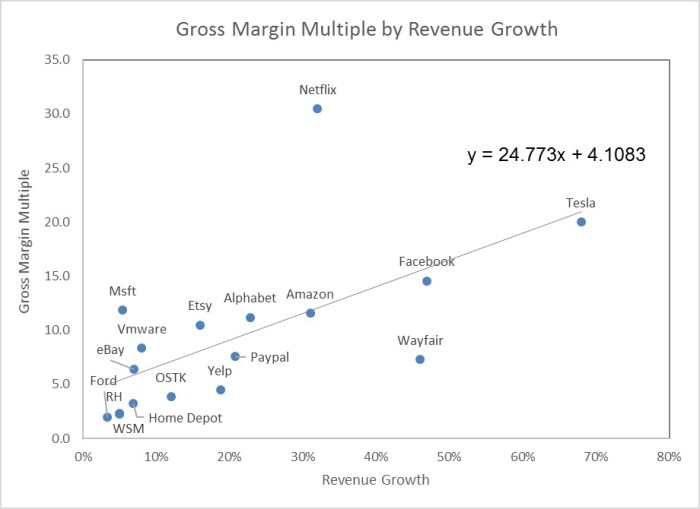

For example, Online advertising has distinct leaders in overall social (Facebook), search advertising (Google), Visual advertising (Pinterest), eCommerce ads (Amazon) and programmatic (The Trade Desk). So, while these 5 companies compete for advertising budget, they each are the dominant brands in their sub-sector with massive networks of users that are difficult to replicate.

Picking the winners

In the first section of this blog, I highlighted six different types of competitive advantages I look for. The companies that I have recently invested in have three or more of these advantages, and on average qualifies for roughly 4.5. On the leadership side not only do all have very strong leadership but virtually all are led by their founder who is an early innovator in their sector.

One other major consideration recently has been the impact of the pandemic. There are three companies that I have previously covered in the blog that I feel benefit strongly: Amazon, DocuSign, and Zoom. Both Peloton and Shopify would be major additional beneficiaries. When the pandemic ends there is widespread views on how such companies will be impacted. On the one hand, many analysts believe some or all of these will experience a reduction in revenue against strong comps. Others, including myself, think that behavior has changed, so while massive growth experienced during the pandemic won’t be replicated, most, if not all of them will continue to grow at a more “normal” rate. The four advertising companies I mentioned previously: Facebook, Google, Pinterest and The Trade Desk have all been impacted by the loss of advertising from major business segments like travel, live events (and associated ticket sellers) and brick and mortar retail. Since Amazon advertising revenue is limited to online sellers it is not affected by loss of ads from these sectors. My expectation is that when the Shelter-in-Place requirements are substantially eased, all four of these companies will experience a jump in advertising revenue. As we reach April of 2021 this jump will be compared to depressed comps and all four should experience above normal growth.

Of companies that are in my 2020 stock pics, surprisingly, Tesla has appreciated well over 600% despite its revenue being lower than pre-pandemic expectations. I believe this is mostly because of the certain shift taking place towards software enabled electronic cars but the stock has also been helped by inclusion in the S&P index. The other company negatively impacted by the pandemic is Stitch Fix. On the one hand, it has undoubtedly gained share as it offers a modern online method of shopping to its very large base of customers, but it is also obvious that people are just not buying that many items of clothes during the pandemic. I expected Stitch Fix to be a substantial beneficiary when Shelter-in-Place is eased, but the market is already anticipating this as we’ve seen it’s begin year value of $25.66, which fell dramatically earlier in the pandemic, rebound nicely to a price of $69 in December 2020…a 170% appreciation year-to-date.

I have also been examining several companies that had recently IPO’d as younger public companies tend to have higher growth rates which in turn creates greater potential future appreciation. So, I considered the various companies that had come public in 2019 to see which ones met my screens. Investing in Lyft and Uber, post IPO, had little interest for me. On the positive side, Lyft revenue growth was 95% in Q1, 2019, but it had a negative contribution margin in 2018 and Q1 2019. Uber’s growth was a much lower 20% in Q1, but it appeared to have slightly better contribution margin than Lyft, possibly even as high as 5%. I expected Uber and Lyft to improve their contribution margin, but it is difficult to see either of them delivering a reasonable level of profitability in the near term as scaling revenue does not help profitability until contribution margin improves. So, I passed on both which proved the right decision as Lyft is still well below the first day’s closing price of $78.29 post-IPO. Uber is now up 27% vs its first day closing price (roughly the same as the S&P index) as food delivery has proven a great business for them during the pandemic. The first of the 2019 IPO class that I bought was Zoom Video, which had a contribution margin of roughly 25% coupled with over 100% revenue growth. It also seemed on the verge of moving to profitability. Four others piqued my interest: Pinterest, Peloton, Slack and CrowdStrike. All of these were growing revenue at a 40% or higher rate, had solid business models and met my other criteria. I’ll discuss these in more detail in my following posts but, on average, they are up well over 300% this year …stay tuned for my 2021 predictions!